I am very happy Richard allowed me to add his articles to my pages, and I think that every rebreather diver should read this information as part of his education!

A learner's guide to Closed-Circuit Rebreather Operations

|

||||

|

Introduction:My interest in advanced mixed-gas diving technology, including closed-circuit rebreathers, stems from my ongoing endeavor to document marine life inhabiting deep coral reefs. Biologists using conventional air scuba have been limited to maximum depths of about 130-190 ft /40-57 m for productive exploratory work. Scientific research utilizing deep-sea submersibles has primarily focused on habitats at depths well in excess of 500 ft /150 m. The region in between, which I have referred to as the undersea "Twilight Zone" (Fig. 1), remains largely unexplored (Pyle, 1991; 1992a; 1996a; 1996b; Montres Rolex S.A., 1996).

|

||||

|

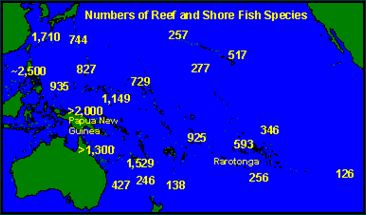

In an effort to safely investigate this region, I designed an open-circuit mixed-gas diving rig that incorporated two large-capacity cylinders, two pony cylinders, five regulators, and a surface-supplied oxygen system for decompression (Pyle, 1992b; 1996c; Sharkey & Pyle, 1993). Using this open-circuit rig, Charles "Chip" Boyle and I discovered more than a dozen new species of reef fishes on the deep coral reefs of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands (e.g., Pyle, 1991; 1994; Pyle & Randall, 1992). The extent of these discoveries was remarkable not only because of the extremely limited amount of time spent at depth (12-15 minutes per dive), but also because Rarotonga lies far from the center of coral reef species diversity (Fig. 2). Given the unexpected wealth of diversity in the "Twilight Zone", it was clear that I would need to conduct dives with longer bottom times in order to adequately explore this region, especially if I was to examine the deep reefs of the more species-rich western Pacific. Unfortunately, transporting large quantities of oxygen and helium to remote tropical islands can be extremely expensive and logistically difficult, if not impossible. The obvious solution was to use closed-circuit mixed-gas rebreather technology.

|

|||

|

In 1994, Cis-Lunar Development Laboratories provided me with two of their MK-4P closed-circuit, mixed-gas rebreathers, so that my diving partner John Earle and I could continue exploration of deep coral reefs. After nearly a year of training in Hawaii, we shipped the rebreathers to Papua New Guinea for a series of exploratory dives on the deep reef drop-offs. Diving from the M/V Telita (live-aboard vessel), we logged a total of 96 hours on the rebreathers, including 28 trimix dives to depths of 200-420 ft/61-122 meters. Although we only intended to conduct preliminary observations during this expedition, we nevertheless discovered nearly thirty new species of fishes and several new invertebrate species (e.g., Gill et al., in press; Earle & Pyle, in press; Allen & Randall, in press; Randall & Fourmanoir, in press).

|

|

|||

Staying alive on a closed circuit rebreatherHaving spent the past two years developing my own procedures and protocols for decompression diving using closed-circuit rebreathers, I have learned some important lessons (Comper & Remley, 1996; Pyle, 1996d). After my first 10 hours on a rebreather, I was a real expert. Another 40 hours of dive time later, I considered myself a novice. When I had completed about 100 hours of rebreather diving, I realized I was only just a beginner. Now that I have spend more than 200 hours diving with a closed-circuit system, it is clear that I am still a rebreather weenie. In my experience, the underlying quality that divers must have to consistently survive rebreather dives is discipline. The first step in exercising this discipline is to realize that it takes a fair amount of rebreather experience just to comprehend what your true limitations are. You should leave a wide margin for error between what you think your limitations are, and what sort of diving activity you actually do. To help new rebreather divers survive the early overconfidence period, I offer these suggestions: |

||||

1. Know your pO2 at all timesWithout doubt, the single most hazardous aspect of closed-circuit rebreathers is the fact that the oxygen content of the breathing mixture is dynamic. With open-circuit scuba, inspired gas fractions are constant. Thus, as long as gas mixtures are not breathed outside their respective pre-defined depth limits (assuming proper filling and mixture verification procedures have been followed) an open circuit diver can be confident that the inspired gas is life-sustaining. One of the fundamental advantages of closed-circuit rebreathers is their ability to maintain an optimal gas composition at all depths. However, the disadvantage of this dynamic gas mixture system is the potential for oxygen content to drop below or exceed safe levels without any change of depth. The real danger is the insidious nature of hypoxia and hyperoxia. Neither malady has any reliable warning symptoms (although see Pyle, 1995), and both can be deadly in the underwater environment. It is therefore of utmost importance that rebreather divers always know the oxygen partial pressure inside the breathing loop. Simply checking the primary electronic instrumentation on a regular basis is not sufficient. Most electronically-controlled rebreather designs incorporate at least three oxygen sensors, and most will provide divers with at least two different displays of the oxygen sensor values. Many people refer to these as the "primary" and "backup" displays; however, I prefer the term "secondary" to "backup" because most backup equipment is used only after the primary component has failed. Instead, the secondary oxygen display of a closed-circuit rebreather should be monitored almost as regularly as the primary display, to verify that both displays are giving the same value. Ironically, the most reliable rebreathers can potentially be the most dangerous to an undisciplined diver. If the primary oxygen control system virtually never fails, then a diver may become complacent about checking the secondary display. Due to the oxymoronic nature of the phrase "fail-safe electronics" (especially in underwater applications), complacency of this sort can have disastrous consequences.

|

||||

|

2. Open-circuit scuba

experience is not as useful for rebreather diving as a good grasp of diving

physics and physiology. Many experienced open-circuit divers who are new to rebreathers may fall into the "trap" of overconfidence. While vast amounts of open-circuit diving experience can increase a person’s over-all comfort level in the water and enhance one’s respect for the hazards of sub aquatic forays, these qualities alone are insufficient for consistent rebreather survival. Diving with closed-circuit rebreathers differs considerably from open-circuit diving in many respects, ranging from methods of buoyancy control, to gas monitoring habits, to emergency procedures. Development of the proper knowledge, skills, and experience takes time and practice, regardless of how many open-circuit dives (mixed-gas or otherwise) one has successfully completed. What is probably the most dangerous period in any rebreather diver’s learning curve occurs relatively early on; after enough time to be comfortable with the basic operation of the unit, but before there has been enough practice and experience to adequately recognize problems and correct them before they become serious (the period when one’s confidence exceeds one’s abilities). In some ways, experienced scuba divers may be at greater risk than non-divers when learning how to dive with a rebreather for the first time, because the initial discrepancy between confidence and abilities will be larger. On the other hand, a good working knowledge of gas physics and diving physiology is probably more important for rebreather diving than for open-circuit mixed gas diving. Well-designed closed-circuit rebreathers will provide users with many ways to control the gas mixture in the breathing loop, and divers must have an intuitive understanding of the effects their actions (gas additions, loop-purges, depth changes, etc.) will have on their breathing gas and decompression status. With the additional control a diver has over the inspired breathing mixture in a closed-circuit rebreather, comes the need for greater discipline and understanding of the dynamics involved. |

||||

3. Training should emphasize failure detection, manual control and bailout procedures.Diving with closed-circuit rebreathers is relatively easy when the system is functioning correctly. Recognizing component failures before they lead to serious problems and knowing how best to respond to various failures is a bit more tricky. The solution to problem response is fairly straight-forward: training regimes should include a great deal of time simulating failure situations and practice of appropriate response actions. Manual control of the rebreather is probably the most important skill to learn; in fact, I recommend that new rebreather divers first learn to control the unit manually, and only be allowed to activate the automatic control system after manual control has been mastered. Unfortunately, even the most well-practiced skills, and all the best backup systems in the world, are completely useless to an unconscious diver. Thus, perhaps even more important than knowing how to respond to a problem is knowing how to recognize a problem before it is too late. The most critical failure conditions a rebreather diver may encounter are hypoxia, hyperoxia (due to failure of the oxygen control system), and hypercapnia (due to failure of the absorbent canister). Although the former two do not provide any reliable physiological warning, some people in some circumstances may detect symptoms of hypoxia or hypercapnia prior to blackout or convulsion. Text descriptions of possible "pre-cursor" symptoms might help but, as any teacher knows, first-hand experience is much more useful. The question is: should a rebreather diver be exposed to hypoxia and hyperoxia under controlled conditions during training? (Obviously, "controlled conditions" would not include a diver experiencing these things underwater, or without trained supervision.) Hypoxic symptoms probably occur with more consistency than hyperoxic symptoms. Furthermore, hypoxia can easily be experienced on dry land using a rebreather with a disabled oxygen injection system, whereas hyperoxia (to the point of convulsion) would require a hyperbaric chamber. Therefore, it seems that experience with hypoxia would be both more useful and logistically more feasible during a training regime than experience with hyperoxia would be. Nevertheless, even for hypoxia the answer to the question is not obvious. While having first-hand experience with symptoms might save a diver’s life in some situations, it might also falsely boost a diver’s confidence in his or her ability to detect the onset of such conditions (i.e., induce complacency). Another consideration is that any exposure to hypoxia likely results in the death of brain (and other) cells. Thus, even with the discipline to avoid the complacency problem, it is not clear whether the benefits of first-hand experience of possible warning symptoms outweigh the cost of lost brain cells during a "hypoxia experience" session. In my case, I believe the experience was well-worth the cost. Less ambiguous is the issue of hypercapnia. Although testing by the U.S. Navy indicates that symptoms of hypercapnia cannot be considered as reliable pre-cursors to blackout, the experience of several civilian rebreather divers (myself included) indicate that they can be considered reliable. One possible explanation for this discrepancy of experience may be individual variation. Perhaps some individuals (e.g., so-called CO2-retainers") cannot reliably detect the onset of hypercapnia, while others (perhaps including the aforementioned civilian rebreather divers) can. If this is the case, it makes a great deal of sense to include deliberate exposure to hypercapnia (again, under controlled conditions) as part of a rebreather training regime. This can easily be accomplished on dry land by breathing off a rebreather without a carbon dioxide absorbent canister installed. |

||||

4. Cover your ass.This is probably the most important piece of advice that my rebreather instructor, Bill Stone, gave to me. This point doesn’t need much elaboration, but is nevertheless vital to rebreather survival. It is fundamentally the same principle that all cave divers and mixed-gas divers should already understand: always have an safe alternate pathway back to the surface. For open-circuit divers, this usually means a second regulator and following "rule of thirds" for gas consumption. On rebreather dives, especially those requiring extensive decompression, the logistics of providing for an alternate means to safely return to the surface, even in the event of catastrophic, unrecoverable breathing loop failure, can be difficult. See the section on bailout procedures below for a description of some of the solutions I have developed for my rebreather dives. |

||||

Procedures and Protocols for Closed-Circuit Rebreather DivingProcedures and protocols for closed-circuit rebreather diving will vary according to specific rebreather models and specific diving conditions and objectives. In this section, I will outline the procedures and protocols that I have developed for rebreather model I use, in the environments that I it. I. System Configuration & Equipment 1. Dives Without Required Decompression Stops Most closed-circuit rebreather dives that do not involve ‘required’ decompression stops will be conducted using a single diluent gas (usually nitrogen or helium). If only one non-oxygen cylinder is carried by the diver on such a dive, that cylinder must be accessible via an open-circuit regulator, and the mixture in that cylinder must contain a fraction of oxygen that will sustain the diver at all depths during the dive (air is usually the easiest choice). Furthermore, that cylinder must be of sufficient capacity that all buoyancy control gas, drysuit gas (if applicable), and rebreather gas needs are met with enough remaining that a safe, controlled ascent to the surface in open-circuit mode can be accomplished with sufficient margin for error at any point during the dive. 2. Dives With Required Decompression Stops Rebreather dives that require substantial decompression times often (although not always) involve more than one diluent gas type (usually nitrogen, helium, and/or a combination of both). More often than not, it would be entirely impractical for a diver to carry a large enough gas supply to complete full decompression in open-circuit mode. This leaves two options: 1) the diver carries a completely independent rebreather system (including independent breathing loop, counterlung, and absorbent canister); or 2) the diver carries enough gas supply to safely reach a staged life-support system (e.g. another rebreather, more open-circuit gas supply, an underwater habitat, etc.) while breathing the carried gas in open-circuit mode. The difficulty with option number 1 includes not only the problem of physical placement of the secondary rebreather, but also the need to monitor and control the gas content within the secondary breathing loop during depth changes. More frequently, one form of option number 2 will be used, in which case much thought must be given to the question of how much of each type of gas will be carried by the diver, and how much will be staged. There are many variables that affect this ratio, including whether or not buddies can be relied upon for auxiliary open-circuit gas supplies, whether or not full face masks are used, whether there is a guideline physically connecting the diver with the staged gas supply, maximum depth and duration of the dive, strength of current, among many others. The oxygen content of the diluent gas mixture(s) should be such that the diver has access to at least one life-sustaining mixture in open-circuit mode at any point (depth) during the course of the dive. Choosing a diluent configuration to optimally meet the needs of the dive is among the most difficult aspects of decompression diving with rebreathers. I have experimented with a wide variety of con-figurations, and have settled upon one basic configuration that I use for almost all dives to depths in excess of about 220 ft (66 m), with total ‘required’ decompression times exceeding about 15 minutes. This configuration includes a total of 80 cubic feet (cf) of gas in three cylinders: one 20 cf "on-board" cylinder, and two 30cf "off-board" cylinders. One of the 30 cf cylinders will contain a trimix that is safe to breathe at the maximum possible depth of the dive. The other two cylinders will include one with air, and one with heliox-10 (10% oxygen, 90% helium); which of these two gases that is in the 20 cf "on-board" cylinder and which is in the 30 cf "off-board" cylinder will depend on the planned decompression profile of the dive. The placement of the staged gas cylinders will depend on a variety of factors (discussed below under the "Bailout" section). Most dives without ‘required’ decompression stops can be safely accomplished using only one oxygen cylinder. If the single oxygen cylinder is accessible via open circuit mode, then dives with limited ‘required’ decompression can also be conducted safely with a single oxygen supply (limited by whether or not the oxygen supply can sustain the diver in open-circuit mode for the duration of the shallowest decompression stops, with appropriate margin for error). Although dives requiring extensive decompression can be conducted with a single oxygen supply (provided a large supply of open-circuit decompression gases can be reliably accessed in an emergency bailout situation), it is usually better to carry a backup oxygen supply on such dives. If any part of a single oxygen delivery system fails on a closed-circuit rebreather, then the diver will essentially be forced to conduct an open-circuit bailout (or perhaps some form of semi-closed circuit bailout), at least for as long as it takes to access a staged rebreather oxygen supply. For dives requiring extensive decompression, I carry two independent oxygen supplies, both contained in 13.5 cf cylinders. Either cylinder contains enough oxygen to complete the entire dive in closed-circuit mode, and both can be accessed in open-circuit mode should the need arise. C. Full Face Mask Considerations The question of whether or not a full face mask should be used on a rebreather dive depends on several factors; primarily whether or not electronic through-water communications systems are to be used, whether or not the dive is conducted solo or with other divers, and to what extent a diver must "go blind" in order to access additional gas supplies (either closed-circuit or open-circuit). In most cases, a full face mask is preferable, but there are some costs to using them. Obviously, if the dive requires electronic through-water communications, a full face mask is probably needed. A full face masks can mean the difference between life and death if the diver blacks out due to hypoxia or hyperoxia, but this advantage is diminished if the dive is to be conducted solo (especially with regard to hypoxia) or with an inattentive buddy. Conversely, a full face mask can increase the risk of drowning if the diver has to "go blind" by removing the mask in order to access additional gas supplies (if the need to access an open-circuit bailout gas supply arises, it is likely to be the least convenient moment to lose one’s ability to see). This hazard can be minimized to some extent by masks and mouthpieces that allow access to additional gas supplies without the need to remove the mask (or the part of the mask that allows the diver to see). In any case, divers should carry a spare conventional mask if a full face mask is to be used. Once the decision to use a full face mask has been made, an additional consideration is what sort of mask to use. Some full face masks have a single airspace that includes the eyes, nose and mouth. Others divide the airspace into two isolated compartments; one for the mouth, and one for the eyes and nose. This latter type of mask (often referred to as a "half-mask") is preferable for rebreather diving for three main reasons. First, a single-compartment full face mask increases the amount of "dead space" in the breathing loop (especially if an oral-nasal cup is not sealing properly), which increases the risk of carbon-dioxide build-up in the mask. Second (as is detailed below), a convenient way to vent excess gas from the breathing loop is by exhaling through the nose; if the compartment that seals the diver’s nose is part of the breathing loop, then the excess loop gas must be vented by some other means. Third, the entire mask can serve as a diaphragm, contracting and expanding on inhalation and exhalation, increasing the overall work of breathing (Rod Farb, personal communication). The relative costs and benefits of full face masks must be taken into account for each different set of dive parameters. Each diver carries a reel with line, and an emergency float of some sort. The length of line on the reel depends primarily on the depth of the dive, and the depth of the first "required" decompression stop, but is usually a minimum of 200 ft (60 m) in length. The ideal emergency float for the sorts of dives I do is inflatable, cylindrical in shape, about 3-6 ft /1-2 m in length and 2-6 inches /5-15 cm in diameter, is bright orange in color, and has an overpressure relief valve. It is often useful to have a small slate with its own pencil attached to the emergency float. This float is used mainly to alert the surface-support personnel that a diver has commenced a bailout from a dive (see discussion below). For all dives involving substantial decompression, additional equipment associated with the surface-support vessel is usually needed. A basic decompression line includes a relatively large float, a relatively thick line, and a weight. The length of the line depends on the decompression profile expected, but is usually at least as long as the depth of the first anticipated "required" decompression stop. A float is attached at one end of the line, and a weight, not exceeding 10 lb. (2 kg) is tied to other end. The end with the weight also has a large clip of some sort (ideally a stainless steel, slip-locking carabiner). Sometimes markers or loops are placed at 10-ft/3 m intervals along the line. This line serves as the decompression "station" (to which additional equipment or gas supplies may be connected), and may or may not be deployed prior to the start of the dive. a. Self-Contained Gas Supplies It is always a good idea to keep extra supplies of breathing gas aboard the surface-support vessel in case of an open-circuit bailout situation. In most cases, supplies of both oxygen and oxygen-nitrogen mixtures (air or EAN) should be on hand, and mixtures incorporating helium may be needed for more extreme dive profiles. In some cases, some or all of this gas will be staged underwater prior to the dive, but in other cases, it will remain in the surface support vessel until (and if) it is needed. Of critical importance is that the diver can reliably reach additional gas supplies, with at least a 30% margin for error, should the need arrive. If only one diver is conducting a decompression rebreather dive (i.e., a solo dive), the volume of total gas supply should be twice that required by the diver for a complete decompression on open circuit. If two divers are conducting the dive simultaneously, then the total supply should be three times the amount that any one diver would need to complete decompression in open-circuit mode. Teams of three or more divers might require even larger gas supplies. The emergency open-circuit oxygen supply could include a surface-supplied oxygen system. Such a system reduces the bulk of equipment in the water, which can be beneficial for extended shallow-water decompression stops (especially for in-water recompression treatment of Decompression Sickness [DCS]). A full discussion of these systems is beyond the scope of this article, but it should be noted here that if two or more divers are conducting decompression dives simultaneously, there needs to be at least one self-contained oxygen supply per diver to guard against the unlikely event that two or more separated divers simultaneously need additional supplies of oxygen. Most other equipment for decompression dives using closed-circuit rebreathers will depend on the particular objectives and environmental conditions of the dive. Two items that most divers should carry are a sharp cutting tool, and one or more sets of decompression tables. The knife should be small and easily accessible by either hand, and the decompression tables should include a variety of depth and bottom-time contingencies, as well as schedules for both closed-circuit (constant oxygen partial pressure) and open-circuit (constant oxygen fraction) decompression with available gas mixtures. In addition to general gas mixing, equipment testing, rig preparation, team briefing, and other obvious pre-dive activities, rebreather divers should perform several additional pre-dive routines. An essential pre-dive test for any rebreather is a loop leak (or "positive pressure") test. This step involves adding gas to the rebreather loop until the over-pressure relief valve vents, and observing for a subsequent drop in remaining loop volume or pressure that might indicate a poorly sealed connection or leak somewhere in the breathing loop. Another test prior to commencing the dive is a verification of the oxygen control system function. Minimally, this test involves flushing the loop with diluent, activating the oxygen control system, and verifying that the solenoid fires correctly. If the unit allows the user to easily adjust the PO2 set-point, the test could be conducted with a low set-point (such as 0.3 atm) to verify that the solenoid stops firing after set-point has been achieved. If this latter test is conducted, it is imperative that the PO2 set-point be returned to the correct value prior to the dive. Beyond the standard checklists frequently used by open-circuit mixed-gas decompression divers, a separate checklist should be developed specifically for the particular rebreather unit that is to be used. Minimally, this checklist should include verification of absorbent type and remaining canister life, accurate oxygen sensor calibration, correct PO2 set-point, oxygen and diluent cylinder pressures, diluent gas composition(s), and correct position (open or closed) of all valves in the system. Additional model-specific verifications may also be required for certain rebreathers. If the descent is abrupt (i.e., a straight, fast descent to depth), the breathing loop should be flushed with diluent prior to commencement of the dive. If the oxygen partial pressure is allowed to increase at the surface prior to the dive (for example, by the action of the oxygen injection solenoid), there is a risk that the oxygen partial pressure in the breathing loop will exceed safe levels during a rapid descent. Correction for this would involve flushing the loop with diluent at depth, which results in an unnecessary loss of potential open-circuit breathing gas supply. If the dive is to be conducted with only helium and oxygen in the loop during the deep portion of the dive, the loop should be flushed with heliox before beginning the descent. Some people (myself included) have experienced impaired concentration when breathing heliox at depths in excess of about 250 ft /75 m following rapid descents. This impairment seems to be alleviated when the nitrogen partial pressure in the breathing loop is maintained at about 2.5-3.0 atm (less than the level at which significant narcosis is usually experienced). There are two basic methods of introducing trimix into the breathing loop. The most obvious is to use a blend of trimix as the diluent supply. The advantage of this method is that the helium-to-nitrogen ratio remains relatively constant; the disadvantage is that nitrogen partial pressure in the breathing loop increases with increasing depth (hence, the trimix must be blended for the maximum depth of the dive, and will be ideal only at that maximum depth). A less obvious method is to blend trimix from separate air and heliox diluent supplies. With this method, the descent begins with a loop full of air, and air as the diluent supply. Upon reaching a depth of about 100 ft /30 m, and allowing the oxygen partial pressure to achieve set-point, the diluent supply is changed to heliox and the descent continues. This results in a relatively constant partial pressure of nitrogen in the breathing loop (calculated as [ambient pressure at time of diluent change] minus [oxygen partial pressure at time of diluent change]). The advantage of this method is that the nitrogen partial pressure does not increase with increasing depth. The disadvantage is that there may be deviations from the predicted nitrogen partial pressure in the event of loop volume fluctuations and loop gas venting (as from mask clearings, etc.). Combinations of these two methods are also possible, but it is vitally important that, whichever method is followed, the software used to generate the decompression profiles (both for real-time decompression and backup decompression tables) take into account the predicted fluctuations of the helium-to-nitrogen ratios. IV. System Monitoring & Control The most critical variable to monitor on a closed-circuit rebreather is the oxygen partial pressure in the breathing loop. The PO2 set-point of the oxygen control system should be no less than 0.5 atm, and no greater than 1.4 atm. The lower limit maintains a margin for error above hypoxic levels, and the upper limit maintains a margin for error below dangerously hyperoxic levels. Although some standards allow for inspired oxygen partial pressures as great as 1.6 atm, such partial pressures would be unsafe set-points on a closed-circuit rebreather for two reasons. First, oxygen partial pressures in the breathing loop can "spike" above set-point during short, rapid descents; and second, rebreather divers should incorporate a more conservative upper oxygen partial pressure limit than open-circuit divers due to the fact that the diver is exposed to that partial pressure throughout the entire dive (as opposed to open-circuit dives, where the PO2 limit is experienced only at the deepest depth of each breathing mixture). Each rebreather diver should become intimately familiar with the rates at which their metabolism affects the oxygen partial pressure within the breathing loop at different levels of exertion, on the specific rebreather that diver intends to use. For example, with the oxygen control system disabled on the rebreather model that I use, the oxygen partial pressure will drop from 1.4 atm to 0.2 atm over the course of about 30-40 minutes at low to moderate exertion levels. My diving partner consumes oxygen at about twice the rate I do at a given workload, and thus causes the same PO2 drop to occur in about 15-20 minutes at the same exertion level. Once a diver knows the oxygen consumption rates, the PO2 levels in the loop should be checked with a frequency no more than one-half the amount of time it would take for the PO2 to drop to dangerous levels. For the example above, if the PO2 setpoint was 1.4 atm, I would check the PO2 in the breathing loop at least every 15 minutes, and my diving partner would check his at least every 7 or 8 minutes. The PO2 should also be monitored during and after every substantial depth change. Divers should also be in the habit of frequently comparing the primary PO2 display with the secondary PO2 display, should note whether or not all oxygen sensor readings are in synchrony, and should note whether the readings are dynamic or static (static readings are often indicative of some sort of oxygen sensor failure). Some rebreather designs allow divers to verify that sensors are providing correct readings; such tests should be performed periodically throughout the dive, and whenever some reason to doubt about the accuracy of the readings presents itself. Although cylinder pressures are of critical importance to open-circuit divers, they are somewhat less critical to closed-circuit rebreather divers. Diluent supply pressure(s) should be monitored to ensure a safe open-circuit bailout can be performed at any point during the dive. Oxygen supply pressure(s) should be monitored to ensure there is a sufficient quantity of oxygen remaining in each oxygen cylinder to complete the remainder of the dive in closed-circuit mode (with a comfortable margin for error). C. Remaining Absorbent Canister Time The amount of time that a given canister of carbon dioxide absorbent will sustain a diver should be clearly and confidently known prior to the commencement of any dive. For dives requiring substantial decompression, there should be at least a 50% margin for error and preferably a 100% margin for error (i.e., an absorbent canister should be able to last one and a half to two times the predicted total dive time). In the absence of reliable carbon dioxide sensors, the ability to reliably predict the remaining life of an absorbent canister can be difficult. The most frequently-used method is a simple "clock" of how much dive time is spent using a particular canister of absorbent. Unfortunately, the rate of this clock can vary among different divers and different workloads by as much as a factor of ten. In the same amount of time that one diver may have completely exhausted the canister, another diver may have used up only 10% of the active life of the absorbent (considering the maximum possible extreme cases). An alternative method of monitoring canister life is to monitor the amount of oxygen consumed. This includes the total volume of oxygen entering the loop, both from oxygen and from diluent supplies. Calibration of this value should be done empirically under controlled conditions (i.e., minimal venting of gas from the breathing loop), with each particular canister design of each particular rebreather (values cannot necessarily be extrapolated based only on volume of absorbent material). A sample size of empirically-derived values should be large enough such that scale of variation can be inferred. Venting of loop gas during dives (e.g., ascents, mask clearings, etc.) will result in a more conservative estimation of remaining canister life. If done correctly, this method of canister life prediction is probably among the most accurate (assuming consistent and proper canister packing techniques and absorbent quality). Divers should be on the alert for potential symptoms of hypercapnia (e.g., shortness of breath, headache, dizziness, nausea, a feeling of "warmth", etc.) during all phases of the dive. If such symptoms are suspected, the dive should be immediately terminated and the ascent should commence. Short-term relief of symptoms following an ascent should not be interpreted as evidence that the canister is functioning properly, because ascents will inherently lead to a short-term drop in the carbon dioxide partial pressure in the breathing loop, and often involve a concurrent reduction of workload (i.e., CO2 production rate). Hypercapnia symptoms might also be a result of improper breathing techniques (i.e., the "skip-breathing" pattern that many scuba divers do, which, of course, confers absolutely no advantage to a rebreather diver). Canister failure can be tested with short-duration periods of high exertion (in shallow water). If a diver feels unusually "starved for breath" after such short bursts of exertion, the canister is probably near the end of its effective life (note, these periods of high exertion should be kept brief, so as not to unnecessarily waste remaining absorbent life). As discussed earlier, it is probably beneficial for rebreather students to undergo first-hand experience with hypercapnia symptoms as part of their basic training course. The volume of gas contained in a rebreather loop (the hoses, canister, and counterlung(s) of the rebreather plus the diver’s lungs) is seldom fixed. I define "minimum" loop volume as that volume of gas occupying the rebreather loop when the counterlung(s) are completely "bottomed-out", and the diver has completely exhaled the gas from his or her lungs. Conversely, "maximum" loop volume is the volume of gas in the breathing loop when the counterlung(s) are maximally inflated, and the diver has maximally inhaled gas into his or her lungs. Although the magnitude of the difference between these two volumes, ([Vmax] [Vmin]), will vary from one rebreather design to another, it will always be non-zero. Rebreather divers must learn to maintain the loop volume close to its optimal level for their particular model of rebreather. If the volume is maintained too close to Vmin, the counterlungs will tend to "bottom-out" on a diver’s full inhalation. If the loop volume is maintained too close to Vmax, the overpressure relief valve will tend to vent excess gas at the peak of a diver’s full exhalation. Furthermore, total loop volume will influence work of breathing due to hydrostatic effects. On rebreather models with a relatively large value of ([Vmax] [Vmin]), the optimal volume should ideally be closer to Vmin; for models with a relatively small value of ([Vmax] [Vmin]), the optimal loop volume should be ideally close to the mid-point. In either case, the diver should maintain the loop volume at whatever level results in the minimum total work of breathing and gas loss. Scuba divers have two main components of "compressible buoyancy"; namely, the buoyancy compensator, and the thermal protection suit. Rebreather divers add to this a third component of "compressible buoyancy"; the breathing loop. Many rebreather divers utilize fluctuations in breathing loop volume as fine-tune control of buoyancy. To maintain a constant PO2 in the breathing loop and a constant loop volume while changing depths, a diver must be skilled in minor gas addition and venting techniques. On descents, most rebreathers will automatically compensate for a dropping loop volume by the addition of diluent. Depending on the fraction of oxygen in the diluent, this may also lead to a concurrent drop in loop PO2 (it should never lead to a rise in loop PO2, because the PO2 of the active diluent at ambient pressure should not exceed the PO2 set-point of the breathing loop). This then leads to subsequent injection of oxygen into the loop by the solenoid, which increases the loop volume. Practiced rebreather divers should be able to indirectly detect changes in loop volume based on changes in buoyancy and work of breathing. Increases to loop volume can be made by the addition of diluent or oxygen (depending on whether the current PO2 is greater than, or less than [respectively] the PO2 set-point). Decreases to loop volume can be accomplished by manually venting gas from the loop, either by exhaling through the nose (except for certain kinds of full face masks), allowing gas to escape from the seal of the lips to the mouthpiece, or dumping gas from a valve somewhere on the rebreather loop. Ideally, a fully-dressed rebreather diver should be neutrally buoyant (or very slightly negative) at the surface, with optimal loop volume, and empty buoyancy compensator. Under such conditions, gas needs to be added to the buoyancy compensator only to compensate for compression of the thermal protection suit, if any. In any case, a diver should be weighted such that he or she is close to neutral when the breathing loop volume is at or near optimal. During an ascent from a rebreather dive, especially a deep dive, the oxygen partial pressure in the loop will begin to drop (due to the dropping ambient pressure). The oxygen control system will likely begin to compensate for this by injecting oxygen; however, except for the slowest of ascents, the solenoid valve will not likely be able to keep up the with drop in loop PO2 due to drop in ambient pressure. Although it may be tempting for a diver to "help" the solenoid achieve PO2 set-point by manually adding oxygen to the loop, this is probably not a good idea in most cases. During the ascent, loop gas will be vented from the breathing loop due to expansion. The diluent component of this lost gas is unrecoverable (it cannot be put back in the cylinders, and it is not used by the body), and assuming a continuous ascent, no more diluent will need to be added to the loop for the remainder of the dive. The oxygen component of the vented gas, however, is wasted especially if the system continuously injects more into the loop to bring the PO2 back up to set-point. This waste of oxygen can be minimized by allowing the PO2 to drop relatively low during the ascent. Obviously, the PO2 level in the loop should be continuously monitored to ensure that it does not drop dangerously low (i.e., below about 0.5 atm). There is seldom any real advantage to adding additional oxygen into the loop manual in a futile attempt to maintain PO2 set-point. My procedure is to allow the PO2 in the loop to drop during the ascent. I manually add oxygen to the loop only if the PO2 drops below 0.5 atm, or when I reach the first decompression stop. At the first decompression stop, I will usually manually add oxygen to the loop to bring the PO2 back up to set-point. Proper manual oxygen addition requires a great deal of practice and training; it’s easy to accidentally over-compensate by adding too much oxygen, escalating the loop PO2 to dangerously high levels. If oxygen is manually injected in large bursts (rather than several short bursts), a "pocket" of high-PO2 gas will move around the breathing loop for several breaths. On most decompression dives involving helium during the deep phase of the dive, the diver will want to flush the helium out of the loop and replace it with nitrogen. I usually do this during an ascent at a depth of about 130-150 ft/40-45 m, and start the flush by venting gas from the loop until the loop volume is at Vmin. I then inflate the loop to Vmax with air, and repeat this cycle at least three times. The partial pressure of any remaining helium in the loop is negligible, and will continue to drop as more gas is vented from the loop during the remainder of the ascent. When I reach the 20-ft /6-m decompression stop, I shut the diluent input supply, and flush the loop with oxygen until the loop PO2 reaches set-point. I will generally remain at this depth until the decompression ceiling has been cleared. If I ascend shallower, I reduce the PO2 set-point to 1.0 atm. VI. System Recovery and Bailout The most valuable skills a rebreather diver must learn are the skills which enable recovery and/or bailout from various failure modes. These skills should be practiced routinely, because a diver should only rarely have to use them in a real emergency situation. A. Oxygen Control System Failure One potential failure mode of most closed-circuit rebreathers is that the solenoid valve can potentially get stuck in the open position. In such a case, oxygen would be continuously injected into the breathing loop, and the PO2 of the breathing loop would reach dangerously-high levels relatively quickly. The first response to this situation (which is usually immediately evident to the diver via audible cues and an increase in loop volume) is to temporarily switch to open-circuit mode. After the oxygen supply to the solenoid has been manually shut, the diver can flush the loop with diluent until the gas is safe to breathe, return to closed circuit mode, and abort the dive while manually maintaining the PO2 in the breathing loop. The obvious response to a solenoid valve that is stuck shut is to abort the dive and maintain PO2 set-point manually. 2. Partial Electronics Failure If either the primary or the secondary PO2 display systems fail at any time during the dive, the dive should be aborted. If the automatic oxygen control system has concurrently failed, the diver should manually maintain the PO2 in the breathing loop following the functional PO2 display. A total electronics failure generally means both the primary and secondary PO2 display systems have failed simultaneously. Although an open-circuit bailout will often be the most appropriate response to this situation (especially if there is no "required" decompression stop and the dive is relatively shallow), there are at least two alternative solutions. Any closed-circuit rebreather can be manually operated as a semi-closed rebreather by the diver. To accomplish this, the diver simply vents every third, fourth, or fifth exhaled breath out of the loop, replenishing it with more diluent. The optimal rate at which exhaled breaths should be vented from the loop depends on the depth, the fraction of the oxygen in the diluent, and the metabolic rate (workload) of the diver. This system is not perfect, but a well-trained rebreather diver should be able to maintain a life-sustaining breathing mixture in the loop until reaching staged bailout cylinders, or a depth where it is safe to use the "Oxygen Rebreather" method (see below), while consuming substantially less gas than a bailout in full open-circuit mode would. This method requires a great deal of practice while the PO2 displays are fully functional to master. Obviously, appropriately conservative decompression schedules should be followed following this bailout method. A more difficult, but more gas-frugal method of maintaining a life-sustaining gas mixture in the breathing loop is to manually mix oxygen and diluent within the breathing loop. During the initial bailout ascent, the diver occasionally adds just enough oxygen to the loop manually to prevent hypoxia from occurring (the proper rate of gas injection can only be learned after much practice and experience). Upon reaching the first decompression stop, the diver blends the first pre-calculated gas mixture. Available to the diver are at least two known gas mixtures (oxygen and at least one diluent with some known fraction of oxygen in it), and two known breathing loop volumes (Vmin and Vmax). Presumably, the difference between the two, ([Vmax] [Vmin]), will not be identical to the absolute value of Vmin. With these known variables, the diver can create (within reasonable limits of accuracy) at least four different gas mixtures. The first gas mixture is achieved by flushing the loop completely with diluent. Once doing this, the diver can manually add oxygen to compensate for the drop in volume of the breathing loop (as oxygen is metabolized and carbon dioxide is absorbed by the absorbent, the loop volume will drop). If a diver is sufficiently sensitive to changes in loop volume, the PO2 in the loop can be maintained relatively constant. The diver continues using this method until reaching a depth shallow enough where the next mixture can be blended. To create the second mixture, the diver flushes the loop with diluent and then achieve Vmin, then manually adds oxygen until Vmax is reached. After allowing the gases to mix for a few breaths, the loop is vented back to optimal volume (if the gas mixture is sufficiently mixed, the FO2 should remain constant). The diver then maintains optimal loop volume with the addition of oxygen. The third mixture involves flushing the loop first with pure oxygen followed by venting until Vmin is reached. The loop is then "topped-off" with diluent until Vmax is achieved, and the loop is vented back to optimal volume after mixing has occurred. This is the most difficult mixture to create, because the diver must breathe in open-circuit mode to avoid hyperoxia during the gas mixing process. The fourth gas mixture is pure oxygen, which can be maintained by using the "Oxygen Rebreather" method outlined below. With two diluent supplies with different oxygen fractions, the number of gas mixtures that can be created increases to 9. With three diluent supplies, there are 16 possible gas mixtures that can be blended. This method is most difficult in deep water, because with a given PO2, the FO2 is relatively small. This means that relatively small changes in loop volumes equate to relatively large changes in PO2. This makes the task of trying to replenish metabolized oxygen considerably more difficult. It cannot be over-emphasized that these methods require a great deal of practice to master. Practice sessions should be conducted while the rebreather electronics are fully functional, so the diver can monitor the various gas flushes and how they affect actual PO2. The simplest and most reliable method of manual oxygen control is to maintain only oxygen in the breathing loop. Unfortunately, this method can only be used at depths of about 15-20 ft /3.5-6 m or less (depending on the maximum PO2 the diver wants to be exposed to). The diver simply flushes the loop with pure oxygen, and replaces and drop in loop volume with more oxygen. Regardless of how precise the diver is at maintaining a constant loop volume, the PO2 in the loop stays constant at any constant depth, and life-sustaining at any depth shallower than about 20 ft /6 m. B. Partial Absorbent Canister Failure A partial failure of the absorbent canister usually means that the absorbent in the canister can no longer remove carbon dioxide from the loop as fast as the diver is producing it, leading to a rise in loop PCO2. If this occurs during a high-workload portion of the dive, the diver may be able to reduce workload during a dive abort and continue in closed-circuit mode for a potentially substantial period of time. If the partial canister failure occurs at a low workload, the diver will likely need to either periodically flush the breathing loop with diluent and/or oxygen in a manual semi-closed mode (as outlined above), or resort to an open-circuit bailout. Once again, only first-hand experience will help guide the diver towards the appropriate course of action. However, if ample breathing gas supplies are available (a they should be in all cases), it is certainly more prudent to complete the dive in open-circuit mode. C. Catastrophic Unrecoverable Loop Failure The "worst-case scenario" for any rebreather dive is a catastrophic unrecoverable loop failure. This can be caused by a severed breathing hose, badly torn counterlung, or completely failed (e.g., flooded) absorbent canister. In such cases, if a diver does not have access to a secondary rebreather system, a bailout in open-circuit mode is inevitable. 1. Dives Without Required Decompression Stops If there is no "required" decompression time, an open-circuit bailout is the simplest solution. If the diluent gas supply was monitored properly, there should be plenty of breathable gas to conduct a slow, controlled ascent to the surface. If the rebreather system allows open-circuit access to the oxygen supply, a "safety" stop can be conducted at a depth of 10-20 ft/3-6 m to reduce the probability of DCS. 2. Dives With Required Decompression Stops As stated earlier, the most logistically difficult aspect of any rebreather dive requiring substantial decompression is accommodating the possible need for completing the full required decompression in open-circuit mode. Two general scenarios that I have developed are outlined below. In both cases, divers carry a total of 80 cf of diluent and as much as 27 cf of oxygen (as described above in the "System Configuration and Equipment" section). Our most frequent diving method involves a "live" boat following free-drifting divers. There are many advantages to this method, a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article. Herein I will describe our standard protocol for open-circuit bailout from this type of dive. |

||||

|

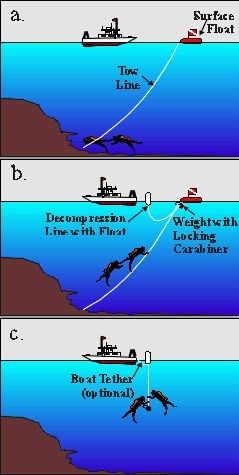

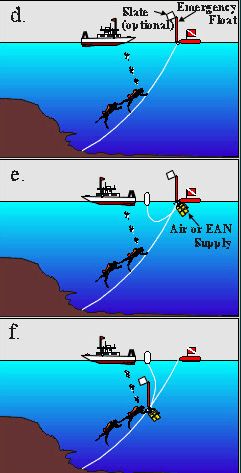

Figure 3a illustrates the normal dive plan: divers pull a "tow line" (made from thin but strong, brightly-colored line) that is attached to small but highly visible "surface float". The boat captain follows this float throughout the course of the dive, keeping a watchful eye for any "emergency floats" that come to the surface. A normal ascent from such a dive (assuming no rebreather failures) involves divers commencing their ascent along the tow-line. At a pre-determined time, the surface-support crew clips a "decompression line" (as described above in the "System Configuration and Equipment" section) to the tow line via the carabineer (or other similar clip) at the weighted end of the decompression line (Fig. 3b). The weight of the decompression line slides down the tow line until the divers rendezvous with it. The divers then detach the decompression line from the tow line (the tow line is either pulled in by the surface support crew, or left to drift until all divers have surfaced), and complete the decompression on the decompression line.Depending on wind and swell conditions, the boat may or may not be physically attached to the decompression line via a "tether" (Fig. 3c). If one or both divers are forced to conduct a bailout in open-circuit mode while the pair is still together, both divers commence the ascent together. The diver conducting the bailout inflates the "emergency float" that he or she has carried throughout the dive, clips it to the tow line, and allows it to slide along the tow line back to the surface. Depending on the particular parameters of the bailout situation, the diver may attach a note of explanation written on a slate that is attached to the emergency float (Fig. 3d). |

|||

|

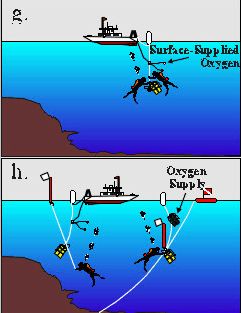

As soon as the float reaches the surface, the surface-support crew responds by deploying the decompression line as described above. In this situation, however, the surface-support crew also attaches a pre-determined configuration of open-circuit breathing gas supply (usually air or EAN) to the weight of the decompression line (Fig. 3e). If both divers are simultaneously conducting an open-circuit bailout, both emergency floats are sent to the surface, and the surface-support crew attaches an appropriate volume of open-circuit gas supply. In either case, the float or floats are usually deflated and returned to the divers along with the open-circuit gas supply by attaching them to the weight of the decompression line and allowing them to slide down the tow line to the divers (Fig. 3f). When the divers rendezvous with the bottom of the decompression line, they detach the tow line as described above, and continue decompression. A additional supply of oxygen is then sent down the decompression line by the surface-support crew to a depth of 20 ft /6 m. If weather conditions allow the boat to be tethered to the decompression line, a surface-supplied oxygen rig (as described above in the "System Configuration and Equipment" section) may be deployed instead of a self-contained oxygen supply (Fig. 3g). The ultimate worst-case scenario involves a separated pair of divers who both independently and simultaneously require open-circuit bailout. If the first emergency float to the surface is attached to the tow line, then the procedures as outlined above are followed, just as if the divers were ascending together (the only difference is that in this case, the diver might not detach the tow line from the decompression line). If a diver becomes separated from the tow line, he or she will commence an ascent to the surface and will deploy an emergency float to the surface, attached to the line of the reel that the diver has carried (as described above in the "System Configuration and Equipment" section). If the diver does not require open-circuit bailout gas supply, he or she writes a note to that effect on a slate, and attaches the slate to the emergency float. |

|

|||

|

|

When the second emergency float is spotted by the surface-support crew, they deploy a self-contained open-circuit oxygen supply down the first decompression line, and deploy a second decompression line to the isolated diver. If there is no note on a slate to the contrary, the surface support assumes the second diver is also engaged in an open-circuit bailout, and supplies gas accordingly (Fig. 3h). In general, the surface-supplied oxygen system is not deployed whenever a diver pair is decompressing separately – it is better to allow the boat freedom to move back and forth between the decompressing divers. If possible, the surface-support crew communicates to each diver the direction of the other diver, so that the divers may swim towards each other and complete decompression together. If the separated diver sends his or her emergency float to the surface first, or if the two divers are both separated (independently) from the tow line, the response procedure is similar, but in the reverse order (i.e., first come, first served). |

|||

|